Several things of late have made me think back to medical school, and try to pin down a vague sense of unease I had there. I think everyone at times finds medical school both fascinating and terrifying in equal measures, albeit to varying extents, but in terms of time most of it, quite correctly, is spent learning about disease. In practice this means a lot of book-learning, and then when you're released fresh-faced and nervous onto the wards (yes, even after

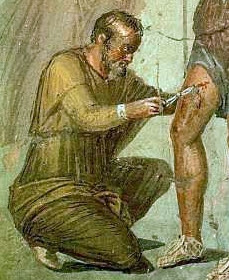

nights like the Daily Fail has recently reported), you talk to patients, take histories to a template in your head, and then try to elicit the excitable beats of the heart, the telltale falling away of the pulse, the kicks and wriggles of pathology, and you learn where to tap and press to make sickness unmask itself on the body.

It is undoubtedly necessary; you cannot presume to treat someone without as firm a grasp as you can muster of what is making them sick, and that means taking advantage of the astonishing, often incomprehensibly brilliant advances made in science which allow us to understand exactly why Aunt Mabel has been getting fat, forgetful, and short on hair, or rather why she has Hashimoto's thyroiditis: humoral antibodies to one or both of thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin cause a type II hypersensitivity reaction which destroys follicles in the thyroid. That is the sort of thing you learn at medical school, and as I say it is necessary: a better question is perhaps the extent to which it is an evil.

The problem I have with it is that the process of taking a history and of eliciting signs distracts you from the person sat in front of you. A group of us saw a man at medical school as part of a teaching session, and took turns examining his neurology: I think he had motor neurone disease, so that he had no strength in his arms or legs, and his muscles were a mass of tiny writhings. We tapped and pushed him, scored his weaknesses and assessed and noted him down, and it was only when a pair of us went back later that we talked about how he was missing his dog at home, a dog he will never have walked again.

The phrasing was intentionally emotive: medical school does divorce you from the person in front of you in favour of breaking them down into a series of manageable, interpretable bits. You learn to produce rabbits from hats, and this is a wonderful skill to gain - but there needs, also, to be an awe in what you are doing, at the repercussions of these signs on the man before you.

This blog was prompted partly by reading about an ambulance technician who

didn't respond to a 999 call as he was on a tea break; the 36-year old involved had a fatal myocardial infarction. Laying aside the obvious questions (what if he was on the loo?), it was the response of the family to the note that the man would be sent for training before restarting work that set me thinking: "Surely they can't teach compassion, so what are they going to give him lessons in?".

I'm not sure that's correct. To some extent the exposure to patients, even through the filter of the structured history and the rigorous examination, obliges you to feel some compassion, and attendance at clinics certainly does. There's a nod to teaching it at university, but my experience of these sessions was that they tended to be smug and pious, that they treated you all like potential Shipmanesque serial killers, and that at their core they reduced compassion to exactly the sort of structured, tick-box exercise which at least serves a purpose in making a diagnosis (the same malaise afflicts junior doctors in the form of the Case-based Discussion or CbD, but that's one for another time).

Exposure is perhaps the key. At the risk of over-reminiscing, probably the single most memorable clinical encounter I had was when a consultant neurosurgeon took us to see a boy who had I think had a tumour of some sort - the purpose of the exercise was to show us what brain-death looked like. He took us in to see the patient with mum at the bedside, obviously in pieces, and asked her permission to examine her son "because it's important they learn". This is the sort of thing that the Medical Educators would regard as appalling, as a terrible invasion of a grieving mother's privacy; in reality she didn't hesitate. It taught me what brain-death looks like, certainly, but it taught me about that in a human context, with mum weeping quietly by the bedside, permitting our presence there because she knew her son would not mind any more and because she trusted the surgeon who had tried to treat him. You can teach these things, perhaps, through exposure not just to signs, but to signs in the context of grief, trust, emotion.

Pathology does not seem to accommodate these things. Certainly, slides of blood cells with things swimming around them which you have to be able to prepare, examine, and interpret do not feel, are not linked to a person despite the paragraph of text describing a notional person they are hung upon. The beautiful, mechanistic intricacies of cell signalling and division, the astonishing techniques parasites use to get into us, and the perpetual arms-race between antibiotic and bacteria do not accommodate feeling. It is only when you put them together and learn to talk of clinical courses as "indolent", "florid", "insidious" that these terms lead you away from the cells to the person in front of you, and you're reminded that these things have a human impact which was of course your reason for doing it all in the first place.

I don't know if there are better ways of doing it; I know there are already numerous bad ones, but all in all medical school seems to work and to produce capable, caring people. Let's hope it stays that way, shall we?